Reclaiming Turkey Day

What Thanksgiving History & Movies Teach Us About the Quintessential American Holiday

Thanksgiving is as American as apple pie. Like apples, the holiday originated in the east and immigrated across the Atlantic hundreds of years ago, but its role in our lives has changed over time, its meaning different to each generation, always evolving.

After 18 years of eating turkeys on Thanksgiving, I will be celebrating my tenth turkey-free Turkey Day this year. That idea likely sounds unsavory to many. But given that we ask fifty million turkeys to “help Americans celebrate their favorite holiday” each year, to use Melanie Kirkpatrick’s euphemism, I think we all have a responsibility to at least consider why we give thanks each year over a bird’s body. In looking back to the holiday’s origins, I’ve come to better understand how the tradition of eating turkeys came about, and I’d argue that leaving them off the Thanksgiving menu is a better way to embrace the natural evolution of the holiday throughout American history.

Thanksgiving’s Origin

Befitting our tradition of reimagining historical events, the 1621 feast we call the First Thanksgiving in Plymouth, Massachusetts, had been lost to time for 200 years. It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that evidence of it resurfaced in the form of first-hand accounts by two Plymouth Puritans. But it wasn’t Thanksgiving as we know it today, and “the Pilgrims would not have viewed the harvest feast of 1621 as a thanksgiving in their understanding of the word,” Melanie Kirkpatrick writes in Thanksgiving. A feast between English Puritans and Native Wampanoag, it was a gathering of new neighbors before, of course, the bloodshed that would come as more colonists arrived.

This wasn’t the first such feast on the American continents, either. Several others have been documented from the mid-sixteenth to early-seventeenth centuries in states as far south as Texas and here in my neck of the woods on the First Coast of Florida. Of course, Kirkpatrick continues,

“The true First Thanksgivings in what became the United States were celebrated not by new arrivals from Europe, but by the indigenous people who had resided in North America for thousands of years. There is no written record of such events, but tribal traditions and ethnological research indicate that Native American tribes practiced thanksgiving rituals at the harvest season as well as at other times of the year.”

The classic iconography of Thanksgiving with which we’re familiar—the Pilgrims’ buckled shoes and hats of black and white, the Native Americans’ feathered headdresses—are not only historically inaccurate but wholly based in our collective myth of the holiday’s origin. This myth persists in movies like Free Birds (2013), Thanksgiving (2023), The Addams Family Values (1993), A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving (1973), and Pilgrim (2019).

Film Spotlight: Thanksgiving (2023)

Watching Eli Roth’s1 Turkey Day slasher, viewers would be hard-pressed to miss the ubiquitous turkey decor around the fictional depiction of Plymouth, MA. The cute little brown, orange, and red caricatures lurk in the background of the entire film, and a turkey-shaped parade balloon plays a crucial role in the story’s climax. Not only does this trivialize turkeys’ role in the holiday, as if the animals enjoy celebrating their own slaughter, but it’s simply inaccurate. (I sense a pattern forming.) While wild turkeys are colorful beauties with lush feathers, the ones raised on farms lack pigmented plumage. They look far more like large white chickens than the images of wild turkeys we use to decorate.

While Thanksgiving includes an abundance of turkeys, Native Americans are nonexistent, perpetuating the same colonial practices of our forefathers. There are no other national holidays—besides Indigenous Peoples’ Day, a recent addition sharing the same date as Columbus Day—where Native cultures are remembered or celebrated. (Though Indigenous Peoples’ Day is hardly celebrated on the same scale as Thanksgiving.) I’d like to hope we could better balance Native representation somewhere between cultural appropriation and total erasure.

Thanksgiving’s Consumers

To call Thanksgiving a religious holiday is akin to calling Easter a secular one; it may have Christian roots, but watching football is about as close to worship most of us get. This alone represents a monumental shift away from the traditional thanksgiving practices of European colonists. Far more integral than praising God today is spending time with loved ones and reflecting on all the blessings we have in our lives.

Detractors, however, claim that acts of beneficence and humility ring hollow with the holiday’s focus on gorging, both on food and other products. With Black Friday sales often starting on Thanksgiving Day, or even earlier in the week, consumerism seems inescapable. Movies like Thanksgiving, Krampus (2015), and Black Friday (2021) not-so-subtly rebuke consumerist crazes by showing how the same people who peacefully gather around a Thanksgiving table turn into monsters (sometimes literally) just a few hours later.

Regardless of whether or not we take advantage of holiday sales (who doesn’t on occasion?), excessive buying doesn’t exactly comport with traditional thanksgiving values. Fortunately, the rise of Giving Tuesday counterbalances some of the excess related to Thanksgiving gluttony—though one could also argue that Giving Tuesday, much like turkey trots, acts as a permission structure to overindulge our bad habits. Giving Tuesday has only existed for a decade, but it draws on the longstanding American tradition of offering charity during the holiday season, dating all the way back to when Pilgrims offset their days of feasts and celebration with days of fasts and humiliation.

Film Spotlight: Planes, Trains & Automobiles (1987)

Like The Humans (2021), Thanksgiving serves more as the background setting in Planes, Trains & Automobiles rather than as part of the plot, yet it can still teach us a valuable lesson about the holiday. A grumpy/sunshine friendship develops as two strangers are forced to travel together from Wichita to Chicago before Thanksgiving. As their luck worsens—from having their cash stolen to their credit cards melting in a fire, leaving them stranded with nothing but the scorched skeleton of a car—they discover that this unexpected experience has forged a deep bond between them.

The audience is left with the message that though it can feel bitter when things don’t go the way we expect, the final result may be even better than what we originally thought we wanted. Extrapolating further, sometimes we focus on the superficialities of traditions—the food we eat, the way we dress, the schedule we follow—and cling to them rather than to the holiday’s essential core. The small parts become representative of the holiday itself, and therefore a threat to that holiday and the personal meaning we find in it. But traditions are ever-evolving, and embracing change rather than fighting it often leads to more meaningful celebrations.

Thanksgiving’s Food

While Planes, Trains & Automobiles represents a sort of anti-consumerism, in which the protagonists find joy in their friendship despite losing most of their physical possessions, there’s no doubt that the ultimate form of Thanksgiving consumerism comes in the form of food. Turkeys take center stage—or center table—thereby turning once-living bodies into products we consume with both our money and our mouths. Kathryn Gillespie writes on this topic in The Cow with Ear Tag #1389:

“Conceptualizing a life as a commodity limits the way of knowing that life: as a commodity, that life is understood in terms of what and how efficiently they can produce. They become a form of living capital and their care…must be oriented around facilitating efficient commodity production.”

In other words, the animals themselves, whether alive or dead, are treated strictly as products to offer maximum output and profit to the people who own them. Thoughts like this are rarely present, or permitted, at the Thanksgiving table, further entrenching the commodification of nonhuman beings’ lives and perpetuating the idea that consuming turkeys on Thanksgiving has always been normal and will never change.

As such, it likely came as quite a shock to most of us to learn that venison was the centerpiece of the First Thanksgiving meal—a bit of holiday trivia that, yet again, isn’t entirely true.

notes in Consider the Turkey that Native Americans had domesticated turkeys some 2,000 years earlier, and the birds were certainly plentiful in the area when Europeans made landfall in the western hemisphere. While it’s possible the Pilgrims and Wampanoag ate turkeys, Melanie Kirkpatrick posits,“Other fowl were more likely to have been on the menu. Duck and geese were so plentiful in the fall that hunters could position themselves in a marsh and fire at dozens of birds floating on the water. There are contemporaneous accounts of early settlers of New England eating swan, crane, and even eagle.”

I doubt the consumption of eagles would go over well today.

In the intervening 400 years, myriad animal-based foods have fallen in and out of fashion on days of thanksgiving, including chicken pie (and basically every other kind of meat pie), cod, bass, eel, mussels, oysters, lobster, and bear.

More interesting (to me, at least) is that almost none of the Thanksgiving staples we know today would have been possible to eat back then. White potatoes hail from South America, sweet potatoes from the Caribbean. (Those of us who prefer to mix in marshmallows with our mashed potatoes would’ve been doubly out of luck.) Cranberries, though native, would have been dried and served as accoutrements—as well as plums and other summer berries—rather than stewed in the sugary sauce we know today. Apples had not yet crossed the Atlantic, and pumpkins wouldn’t have been baked into decadent desserts.

Alternately, we can say with certainty that this feast, and the Pilgrims’ new colonial diet, would’ve been abundant with seasonal native plants like the Three Sisters—beans, corn, and squash—a staple of Indigenous diets and adopted by colonists.

Unlike legumes and vegetables, there’s nothing “seasonal” about harvesting turkeys’ flesh; there’s no time of year when they’re ripe for the killing, especially today when turkeys are born and slaughtered every day of the year. The very idea of one solitary food being served across the entire country, from the rainforests of Washington to the deserts of Arizona to the plains of Oklahoma to the swamps of Florida, homogenizes the overwhelming diversity of edible flora in the United States.

Film Spotlight: Turkey Hollow (2015)

When the central family arrives at their Aunt Cly’s house for Thanksgiving in this Lifetime movie, to say I was shocked when Cly started admonishing them for eating meat would be an understatement. Sure, Cly is the stereotypical aging hippie, but she’s also the hero, not the conniving turkey farmer next door. She and her family work together to expose the farmer’s animal abuse, thereby saving his flock of turkeys, and they celebrate together with a plant-based Thanksgiving feast despite their initial misgivings about her unusual diet.

Turkey Hollow shows that the holidays when something special happens, when we do something new and different, are the ones we remember most. They create memories we cherish for the rest of our lives.

Thanksgiving’s Future

Regardless of how you celebrate Thanksgiving, the traditions we hold dear exist more by random chance than by a long-held devotion to particular holiday practices. The fact that we eat turkeys rather than eels on the fourth Thursday of November is likely because it’s easier to farm land animals than aquatic ones, not because there’s something inherently Thanksgiving-y about this one species of bird. As time passes, we pick and choose which traditions we keep and which we leave behind, often unintentionally.

If we want to honor the tradition and spirit of the First Thanksgiving—whether you consider it to have taken place millennia ago by Native Americans or by the colonists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries—there’s nothing precluding us from extending its spirit of grace to everyone, regardless of species. For those of us deeply connected to more modern traditions, we can still look back on all our joyful Thanksgiving memories with love in our hearts, yet keep turkeys off our plates as we form new memories in the years to come.

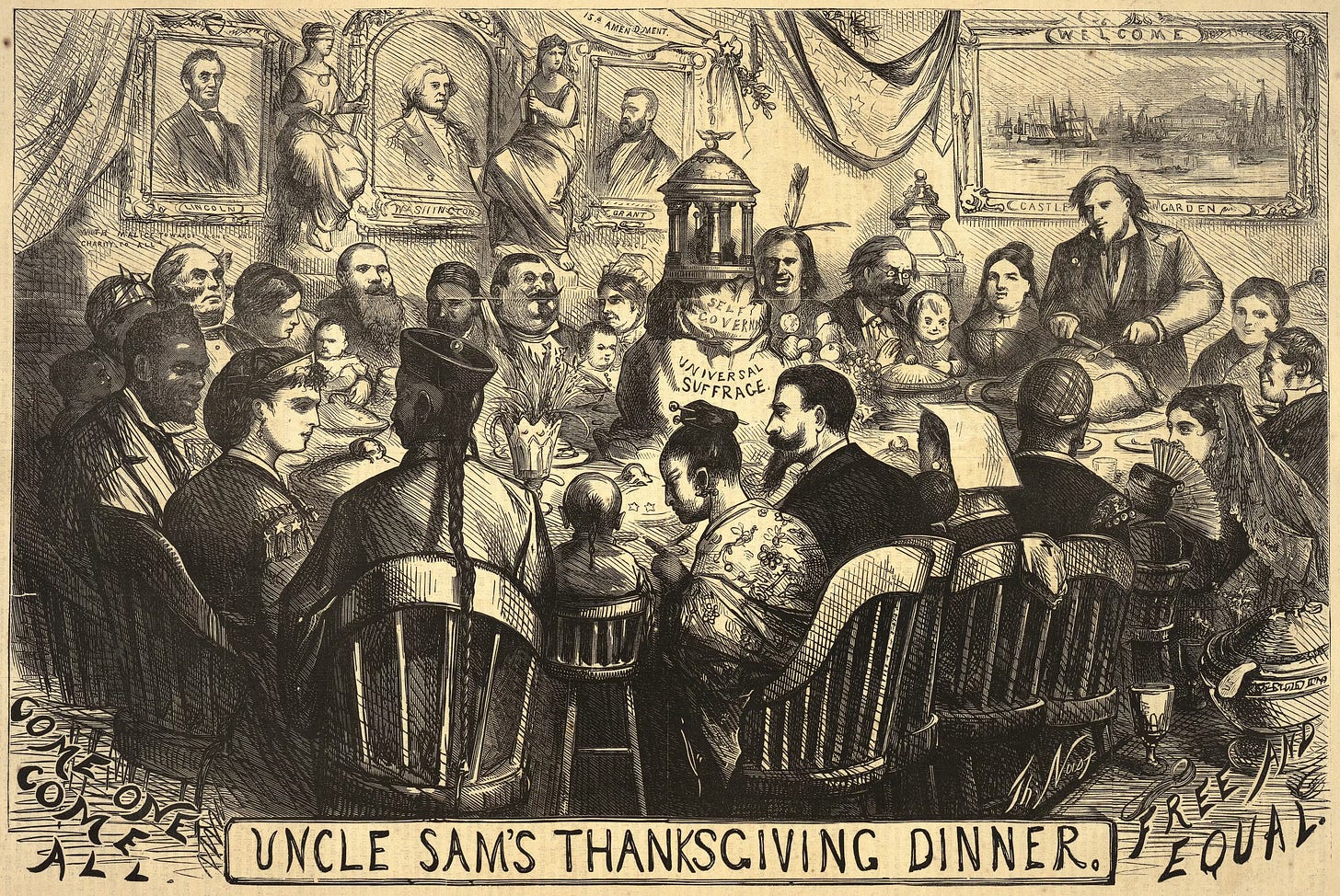

I found Melanie Kirkpatrick’s words on Thomas Nast’s 1869 cartoon “Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Table” particularly prescient: the drawing shows that “every American has an equal right to sit at the Thanksgiving table.” Perhaps the twenty-first century’s version could include all the other Americans, our animal cousins who also call this land home, around the table with us rather than served atop it.

To be as American as apple pie is to celebrate the fusion of histories and cultures that make our country special, and, in doing so, create something new. Apple pie shows us that there’s nothing static about the quintessential American holiday, and that the only immutable Thanksgiving tradition is that those of the future will look far different than those of today. The only question then becomes: How?

On my mind: ‘Twas the Night Before Thanksgiving by Dav Pilkey

In this delightful little picture book (by the author of Captain Underpants, no less), a class trip to a turkey farm takes an unexpected turn when the students choose to rescue the turkeys rather than eat them. I love that this story not only encourages compassion for these birds but also shows children that they can take action when they see injustice.

Roth also advocates for animals in his free time, appearing in PETA ads and occasionally posting on social media. His debut documentary, Fin, draws links between declining shark populations, the fin trade, and industrial fishing.

Such an interesting perspective! It's fascinating how history and media have shaped our collective understanding of the holiday. I always think about how much the narrative has evolved - and how much is still left out. Thanks for sharing this!

Great article, Elise! I shared a link to this and your movie recommendation on Bluesky: https://bsky.app/profile/joyfulgrowth.bsky.social/post/3lbujpbkbds2g.

Your publication's topic is so important! Having positive animal advocacy portrayals in fiction changes the story. :)