Welcome back to another Wizard of Claws interview!

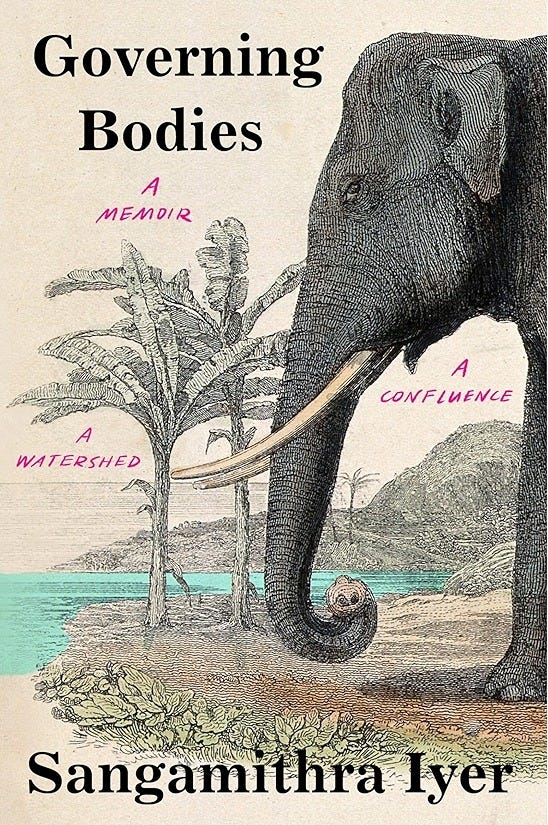

The first time I heard of Sangamithra Iyer, I knew she was one of my people. The way she talks of writing, of animals, and of the power of literature to change the way people think about animals speaks directly to my soul. As such, it’s a great honor to have her here today discussing her new memoir, Governing Bodies. This book is many things, and merely calling it a memoir almost doesn’t do it justice. To understand what this book means, you must think deeply about what exactly a memoir is. It is the author’s life laid bare on the page, a reflection on their deepest thoughts and a dissection of what they mean. It is both intimate and personal and also vast and worldly. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did!

General Questions

Can you share a little bit about yourself, including how you came to care about animals and creative writing?

Caring about animals has been a part of me for as long as I could remember. My parents immigrated from India, and I was the lone vegetarian in my classes who also opted out of dissection. I am proud of this younger me, for not conforming to norms, at a time when it was very difficult and lonely to be different. I think animal rights is where my courage comes from and where my sense of justice was first formed.

In high school, I became head of our animal rights club—Students Against Animal Violations and Exploitation (SAAVE), where we would protest fur and stencil storm drains to protect aquatic animals.

I ended up studying and practicing civil engineering, but I kept looking at opportunities to volunteer for animals. I was an avid reader, and loved reading books about animals. I was looking to find my own way to work that benefited our fellow beings. When I read Roger Fouts’s book, Next of Kin in college about Washoe, the first chimpanzee to acquire American Sign Language, it changed my life, and led me to other volunteer and activist opportunities. Creative writing came later as extension of that activism.

Many of us have childhood dreams of becoming writers. When did you decide to give it a shot?

I had volunteered my engineering skills for a primate sanctuary in Cameroon in 2002. Upon returning to the U.S., I met the editors of Satya Magazine at an animal rights conference in D.C. I was invited to write about my experiences with orphaned chimpanzees in the forest of Cameroon. That was my first published article, and my entry into the professional world of writing in 2003. Soon after, I quit my engineering job to become an editor at Satya Magazine, which focused on the linkages between animal advocacy, social justice, environmentalism and veganism. It was the perfect job that didn’t feel like a job. It felt like being part of an amazing community.

It closed in 2007, and I had to figure out what I wanted to do next. I pursued an MFA in Creative Writing while working full time on water protection. That is when I started working on my debut book that was just published: Governing Bodies: A Memoir, A Confluence, A Watershed.

Most animal advocacy focuses on creating tangible changes in the real world. What role can the arts play in changing how people think about animals?

I think the arts—and literature in particular—is a place where we can dwell in the difficult questions. Literature can hold grief. It can help us imagine another way forward. The arts can nourish our souls as we work on those tangible changes.

What is The Literary Animal Project, and how did you come up with the idea to start it?

The Literary Animal Project is a habitat for curated conversations, questions, and writings that explore how animals are and can be portrayed on the page, beyond symbols, metaphors and mirrors. It will spotlight multi-species storytelling, The goal is to inspire dialogue and create community around the art and ethics of writing about animals and encourage storytelling and discussion that spotlight multi-species perspectives, animal agency, and activism.

Your essay in The Edinburgh Companion to Vegan Literary Studies, “Through a Vegan Lens: The Challenges and Ethics of Exposé,” was itself like an exposé of Eating Animals and The Omnivore’s Dilemma. How can authors better balance truth and dramatic storytelling in nonfiction?

Thank you for reading that essay, which explores the Exposé and offers a critical look at those texts. When a writer is working to expose difficult truths like violence towards animals, there is often a discomfort that both the writer and reader face. The challenge for the writer is to figure out how to write to readers so they will continue to read and not shut the book. But the aim should be not only to relieve the writer and reader of the discomfort—but also the animals! We need to remember that is the goal for our storytelling.

In your essay “Are You Willing?” from Writing for Animals, you share the story of a man who cared for the ants in his cell at Guantánamo Bay. In what ways can stories about humans encourage readers to care more deeply about animals?

This is also something I am interested in exploring more with The Literary Animal project—how do we capture what it means to be a human who thinks and feels deeply about other animals. There is much solidarity I feel when I encounter this on the page. The essay “A Handful of Walnuts” by Ahmed Errachidi and his care for these tiny vulnerable creatures in Guantanamo Bay, where he and his inmates were routinely abused, was so moving to me. Even in the harshest and most unjust conditions, the instinct to love and care for all life persists.

Do you have any advice for vegan authors who’re writing about animals — either fiction or nonfiction — for getting an agent or getting traditionally published more generally?

My path was circuitous, long, and the opposite of a traditional route. Early on in the process, I had spoken to several editors and agents, who appreciated my writing, but they had thought I was trying to do too much, and wanted me to write a simpler book. I had to tune out all these voices and return to the work and my vision. The heart of my book is the connections between these seemingly disparate threads.

Several years back, my friend Geeta Kothari, nominated me for the Aspen Summer Words Emerging Writing Fellowship. One of the judges that year was an acquiring editor at Milkweed Editions and she had reached out separately to see if I was working on a book and thought that Milkweed might be a good home. What I really loved was how she saw the fullness and possibility of the book- and how it connected family history, water and animals together.

I finally found and editor and press who appreciated this vision, and I got my agent after.

We all find our own way and it’s important to learn how to become the best advocate for your work in the process.

Story Questions

You begin Governing Bodies with a poem that ends in: “What harms one body harms all bodies./ Like tributaries to the same river, our stories are entwined.” This is a memoir about confluences, about the ways your story intersects with others’. For those who haven’t read it yet, can you explain the significance of confluences to the book?

Confluences are at the heart of this book. The book sits at so many confluences: prose and poetry, art and science, personal and planetary grief. I weave family history, the rights of animals and the memory of water. The book is also structured like the Triveni Sangam—the confluence of three rivers. Each part is written as a letter. One to my paternal grandfather who like me studied civil engineering and later pursued activism, the second to my late father who shared my fondness for writing and animals, and the third to the reader.

Towards the end of the book, you wrote, “The river reminds you to be a storyteller and that your story is not just for you.” When did you realize that you wanted to write a memoir? How did you gain the confidence to know that your story was worth sharing?

I started an MFA program at Hunter College after Satya Magazine closed. At the time, I thought I was going to write a more traditional narrative nonfiction or journalistic book. Perhaps like a vegan version of Michael Pollan or Eric Schlosser. I had the deep pleasure of studying with Louise DeSalvo who founded the program in memoir. I loved Louise’s take on memoir as an ethical and moral imperative. She also instilled upon us that memoir is a corrective to history.

Memoir was the way I could connect all the subjects I wanted to connect, because I was the link between them all. Memoir is also a way of tracing the way we think and the connections we make. It is governed by association more than chronology and can function like poetry. While I was writing a memoir and a personal story, it was always a story about connection to the larger world. It is this confluence between the self and the world that is of great interest to me.

There is often a lot of misunderstanding of the genre of memoir. I wanted to reclaim it as literature that helps make meaning of our lives and bear witness to these times. It can also hold history, poetry, essay, epistolary, reportage within it. Like water, it is so expansive.

I’ve tried so many times to come up with a question about your choice to write the book mostly in present tense. I want to connect it to the constant yet ever-changing nature of rivers; to lineages, to “how they go both ways” by keeping “our deceased ancestors alive”; to divination, to how we look to the past to divine the future, to how we look to the earth to divine meaning in life. Instead of trying to weave all that together, I’ll just ask: Why present tense?

In my book, I connect different times and places and generations, and geologic epochs. QM Zhang, a writing mentor, said “we think of memory as a creature of the past, yet it lives in the present.”

While I look at the past and go back decades, centuries, and even millennia, my view is shaped by the present and where I’m standing. There’s also something about present tense related to the shape of the rivers. The present tense captured the flow of the book, and I was able to move and meander with it.

Upon learning that your grandfather taught his children classic British literature, such as Shakespeare and Tennyson, you wrote to him: “Initially, I find it curious how you, who quit the British in Burma to join the Freedom Movement in India, showered your children with the oppressor’s literature. But I now realize that relationships are complicated, and perhaps noncooperation need not apply to poetry.” Carrying on your grandfather’s tradition, you reference other writers throughout the book. Even if their words aren’t related to animal rights or your own life experiences, you absorb them and impart your own meaning onto them. Do you think our movement could be more effective if we read more, read broadly, and read with intention?

Absolutely. Reading widely and broadly has been such a gift to my own work. When I worked at Satya magazine, we were looking at the linkages across many areas of social justice. I often find reading about other causes and activists, even if not specific to animals, has a resonance to animal rights, and there is always something we can learn from other areas. I also think literature holds the whole array of emotion and can carry fears, doubts, grief, desires and loves. We must navigate all these in animal rights and reading broadly can help us find ways to do that. Reading with intention and reading generously are also key. We should approach each text and look for possibilities which might expand our own thinking and storytelling. And even if we disagree strongly with a text, it can be helpful to recognize how that work helped clarify our own thoughts and feelings.

Do you think the animal rights movement makes effective use of storytelling as an activism technique? How could we better use stories to advocate for animals?

I think storytelling, literature, and art can be effective tools in activism. Its success is difficult to measure and document, so the results are often invisible. All I know is how meaningful literature has been for me. I have been impacted by the writings of others from other times and centuries. We may not know when or where or how our words will reach who they need to reach, but we must put them out there.

You wrote, “Do not make a scene. You have to make a scene. So much of activism is toggling between these two states.” How can animal advocates find a sustainable balance between these states in their own lives?

This is something all of us navigate in almost every moment. We read the room and the audience and must decide what each moment demands of us. We make mistakes along the way and learn from them. Whether making a scene or not making a scene, I am leaning towards generosity and vulnerability versus judgement or cleverness.

I felt increasingly anxious as I read the chapter in which you visited a chicken slaughterhouse in India. In earlier chapters, animal exploitation and suffering came up, but this was the first time we, through you, were going to actually see some of the world’s worst animal cruelty for ourselves. Almost as if I were there, I wanted to turn away and spare myself, and I dreaded flipping to the next page as you progressed through the slaughterhouse. You generated all these feelings in me without ever showing the chickens’ slaughter. How can writers evoke those kinds of emotions in their readers without hitting them over the head with depictions of animal suffering?

I thought about this a lot. This was the challenge for me, who as a writer and witness, did not want to stay in these places of horror. I also did not want to look away. How do we look and protect our hearts? It was important for me to create a kind of sanctuary for my reader too. If you look at the rivers in the table of contents, there are these rock islands where I have shorter, more meditative chapters, that often come after witnessing difficult material. I have moments of pause within the page. I want to be inviting and generous towards my reader who I am asking to come with me on this sorrow-filled journey.

Your process of relearning Tamil changed how you think about other areas of your life. In what ways does language — both the literal language we speak and the words we choose to use in that language — influence the way we all think about the world?

Language is so connected to how we think of the world. We are losing so many ancient languages, and I am worried about all the knowledges they contain that may be lost. In my research into Tamil, I learned about an ecological grammar that was contained within the language itself. In another book, I recently read, Marginlands by Arati Kumar-Rao, she writes about a community in an arid area, that only gets 40 days of rain a year, and yet they have 40 different words for clouds.

In my book I draw from words in other languages that convey this connection to the world more deeply than I know English to be capable of.

As I read, I was in awe of how connected to the world you are, and I began to feel ashamed of how disconnected I am. But then I realized that wasn’t true. I may not have been to the same places, studied the same languages or histories or literature, but I’m connected to the world in different ways. And in these ways, I, and we all, can find more connections with others, with the world and all its inhabitants. How can readers recognize, appreciate, and learn from the confluences in their own lives?

We all are so connected. In our workplaces I am hoping we can take down silos between disciplines or groups. There is so much we can learn from each other.

There is a Japanese primatologist I write about in the book—Kinji Imanishi. His approach to science was different that many in the west. Instead of focusing on differences, he was looking for connections with all the other beings, and by doing so, he recognized their cultures.

During my book talks, I have been experimenting with an audience confluence activity, where I give the audience a few minutes to interact with a person they don’t know and chat about something that resonated with them or why they came. I found that these strangers found connection even only having a few minutes to chat. Confluence are generative, they continue to provide more connections

Your acknowledgements has to be one of the longest I’ve read in any book. It’s like a confluence in itself, a coming together of all the names of people who aided you on this journey. How important is community to writing, activism, life, everything?

Acknowledgments are my favorite thing! I love reading book acknowledgments. I introduce a concept in my book that a Burmese water activist shared with me: Kalyanamitra. It means spiritual friend or co-worker, and the premise is that two people meditating side by side is more powerful than each doing it alone. I called my Acknowledgments section, “My Kalyanamitra,” listing all the people who have sat alongside me on this journey. Writing is a very solitary act, but we don’t do it alone. Same with activism. What has given me strength and courage is finding that group of people who see you, bear witness to your life and labors, and with whom I can share both daily delights and deep sorrow with. All this work, whether it be writing or activism, can be very difficult and lonely, but it’s also necessary. We need community to support each other doing this vital labor.

You wrote that Next of Kin was your “Spark Book,” the book that started your journey that led to the publication of Governing Bodies. It prompted two questions for you: “How can we learn about, and from, other animals without harming them? How do we repair the harm we have already caused other species?” So, how can we do those things?

These are the questions I carry with me every day and ones I will likely be trying to answer for all the days that come. In my book I discuss three concepts that have been my guideposts. One is satya, or truth. Part of this is always orienting towards seeking truth and holding multiple truths. Another is ahimsa, or this absence of a desire to cause harm. Living with compassion, empathy, and generosity are key. And the final, is what I discussed above, Kalyanamitra and fostering this community because we can’t do this alone.

Final Questions

How can readers find you and your work online?

Website: sangamithraiyer.com

Substack: literaryanimal.substack.com

Social media: @literaryanimals