Interview: Tracey Winter Glover

On chickens, animal communication, and the end of the world

Welcome to the very first Wizard of Claws author interview, with the fabulous Tracey Winter Glover!

In addition to being an author, Tracey is the founder of Sweet Peeps Microsanctuary and ARC, director of two short films, and writer of

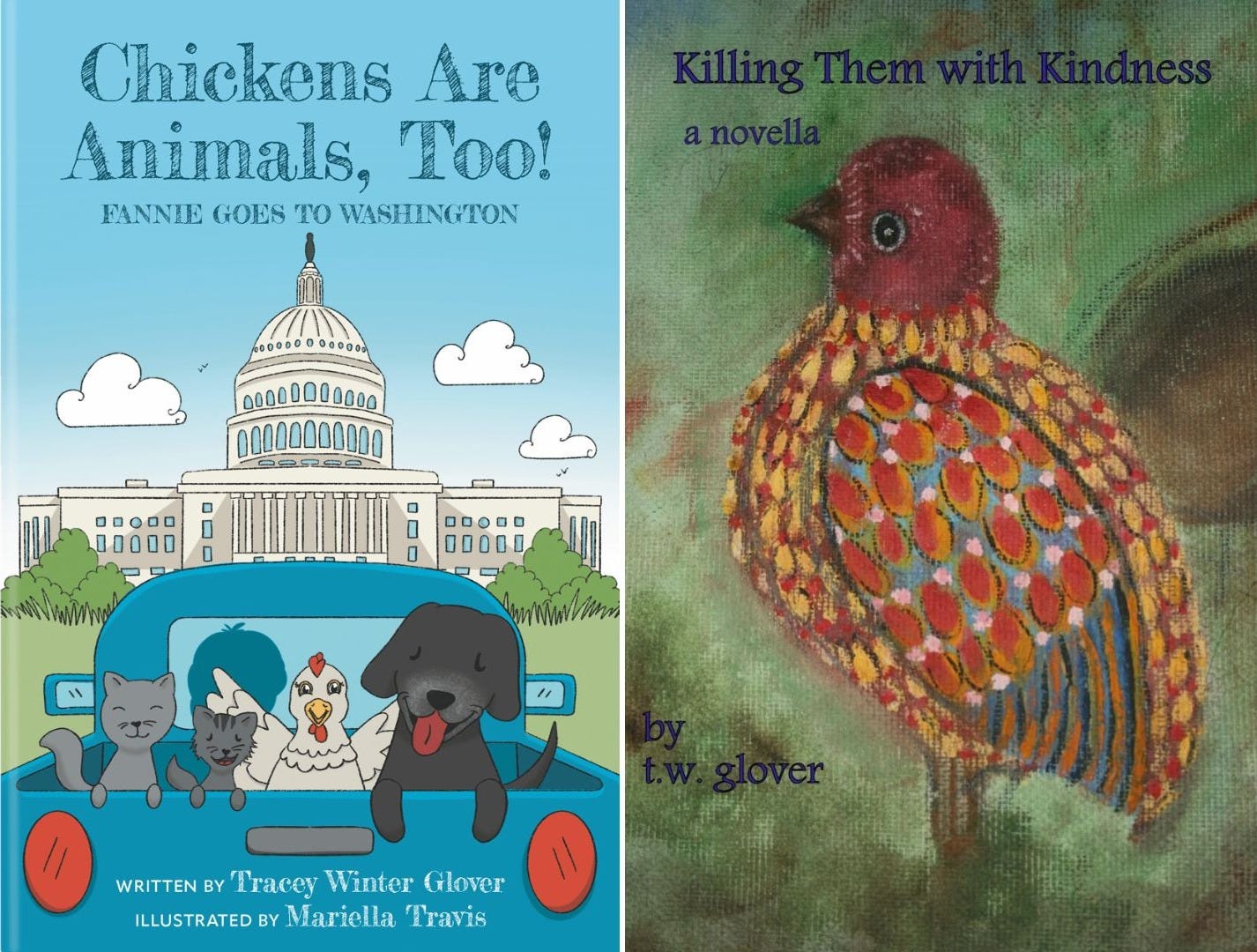

here on Substack. Today, she’ll be sharing more about her most recent book, Chickens Are Animals, Too! Fannie Goes to Washington, and her earlier novella, Killing Them with Kindness.Chickens Are Animals, Too! is a children’s book that follows a flock of rescued hens to Washington, DC, as they kindly ask Congress to be acknowledged as animals and legally protected.

Killing Them with Kindness tells the life story of Olly, a burnt-out animal rights activist who moves to Costa Rica and starts a family. There, he meets the narrator, Moon, and the two debate the ethics of pushing a button that would effectively end all life on Earth.

Questions with potential spoilers have been labeled

General Questions

Can you share a little bit about your background, including how you came to care about animals and creative writing?

I trace my love of animals back to my childhood and my father in particular. My parents divorced when I was little, and we had companion animals at both houses, but my dad was the real animal person. We had dogs and lots of cats, plus fish, mice, bunnies, and snakes. And my dad was always bringing orphaned baby birds home from work for us to care for. I have some really powerful memories of him teaching me how to be gentle with the animals, how to care for them. I learned from an early age to care deeply for animals and to treat them with compassion, tenderness, curiosity, and wonder. Though it wasn’t until I was about 16 that we ever considered that we maybe shouldn’t be eating these animals who we loved so much. My dad and I both went vegetarian then but both returned to eating animals at some point as we battled a lot of denial, until years later when I went fully vegan, knowing this time it was forever, and my dad went vegan not long after that. My mom also went vegan a couple years later. My dad passed away a few years ago. But my mom is a healthy, strong 82-year-old going on 20 years as a vegan.

I also started writing at a pretty early age. My earliest memory of creative writing was probably in middle school. I remember writing some embarrassingly bad poetry. And then have really written on and off my whole life. It’s always something I’ve come back to, something that feels somewhat necessary for me as a way to process life and communicate my experience of it, whether that’s in fiction or non-fiction.

Many of us have childhood dreams of becoming a writer. At what point did you decide to actually go for it?

I’ve kind of jumped into the idea of being a writer a few different times, but then repeatedly let it go for long stretches, thanks to a lot of imposter syndrome, self-doubt, and what seemed like a never ending stream of rejections from literary agents, various publications, and publishers. But I’ve always come back to writing. A few years ago, after letting it collect dust for probably a decade, I pulled The Artist's Way by Julia Cameron off the shelf and worked through it. It was really liberating and inspiring and helped me set aside a lot of the self-doubt, have more fun with writing, and embrace the idea that I am a writer.

Most animal advocacy focuses on creating tangible changes in the real world. What role can the arts play in changing how people think about animals?

I think the root of all the suffering that we cause to animals and all the harm we do to the natural world is a worldview that sees animals as inferior, that sees the natural world as something to be exploited. All the horrors we inflict on non-human animals can be traced to a fundamental assumption of human supremacy. So in order to create a better world for the animals, we need a real paradigm shift. I think the arts can play a major role in questioning the status quo and helping reframe our relationship with animals.

All those tangible changes we want to see would come naturally if people understood our true connection with non-humans and nature as a whole. I think if we could dismantle all the ideas at the foundation of our hierarchical view of the world, the hierarchy-based exploitative practices would fall away. Writers and filmmakers and other artists have a really important role in helping people see truth, see past the cultural conditioning and reconnect with our innate compassion, and our true interconnection with the other beings with whom we share this beautiful earth.

Do you plot out your stories beforehand, or do you prefer to just start writing and see where the story takes you?

I’m more likely to do an outline for non-fiction than I am with fiction. I think generally with fiction, I get an initial spark of an idea in my head, get that down on paper, and then start fleshing it out to see where it goes.

Any advice for aspiring authors to improve their craft, especially as it pertains to writing about animals? Any advice for aspiring filmmakers?

You have to write to be a writer and make films to be a filmmaker. I think the first step is just doing it. The more we write, the better we get at it. It’s generally true for everything we do. As I mentioned, I worked through The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron about a year ago, and started doing morning pages, where you just free flow journal 3 pages, which was like a revelation for me.

I also think sharing our work with people who can provide feedback, as scary as that can be, is really helpful. So having a great editor or other writer friends—or for filmmakers, other filmmakers—who can give honest feedback is invaluable. And reading! Reading is essential. I’ve also done some workshops in the past that were super helpful. And if we’re writing about animals, we need to make sure we know who they are. So we need to spend time with them, ideally in spaces where they are free to be themselves and express their innate nature.

Story Questions

What inspired Chickens Are Animals, Too!, and when did you realize you wanted to flesh out the idea into a book and get it published?

I was on my way to Louisiana State University’s small animal clinic with a sick rooster named Parusha when I first got the idea. It’s about a four-and-a-half-hour drive, and although we have local vets who see the chickens, whenever we have a really tough problem, we go see the avian specialists at LSU. I often get ideas when I’m on those long drives. I started narrating a note into my phone about this possible story idea and then it just kept coming and by the time I got to LSU it was almost finished. Parusha had to be hospitalized overnight for surgery on a bad bumblefoot infection that just wasn’t healing. So while he was at the clinic I checked into a hotel for the night and pretty much finished the story. So much of what I write feels laborious, and takes an almost excruciating amount of time to research, and restructure and rewrite, but not this story. It just came out.

It was largely inspired by the chickens at my sanctuary. Fannie, who is the main character in the book was modeled on the real life Fannie. I tell the origin stories of the chickens who arrive at the sanctuary in the book. The fictional Fannie has a different beginning than the real one, but all of the stories in the book are based either on the lives of the animals here or at other sanctuaries I know. In the book, there's a group of chickens who survive a tornado. That’s pretty much all the true story of a flock here we call the Georgia girls. It was during the pandemic when a tornado hit a factory farm about six hours north of me. Thousands of chickens died. Others were literally bulldozed with the wreckage, but activists were able to rescue a couple hundred, and six of them came here. They, and their story, made it into the book.

I also tried to channel the personalities of the chickens here at the sanctuary into the book’s characters. I want so much for people to know who they are because they’re amazing, sweet, personable, funny, joyful, smart individuals. My story covers some hard truths about life for chickens, but ultimately it’s about changing the world and making progress. It has a happy ending. And I think largely I wrote it because I needed a happy ending. I needed some hope. I didn’t initially set out to write a children’s book. I just wrote a sort of childlike fantasy with a happy ending. And it turned out it is really a kids book, though I think it will appeal to animal lovers of all ages.

I didn’t honestly expect that it would get published! I only sent it out to a couple publishers who I know publish vegan kids books, and to a couple other very small environmentally focused publishers, and I was absolutely ecstatic when one of them, 12 Willows Press, responded to say they wanted to publish it.

This is your first middle-grade book. Why did you think Fannie’s story was best suited for a younger audience?

I don’t know that this is the best way to go about things if you want to get published, but I just wrote the story that was in me, and then once it was out on the page, we figured out who the target audience would be. But that said, I really like that it is geared for middle-grade kids because these are kids who are becoming their own people, kids who are starting to make more decisions for themselves, kids who can start to see that they are capable of impacting the world, and they’re also still young enough that their hearts haven’t yet been so hardened by a society that tries to rob us of our compassion.

How did you come to work with your illustrator, Mariella Travis?

Mariella was someone my publisher already had a working relationship with, so I just got lucky!

The human lead, Abbie, names Fannie after her great-aunt, but are there any other stories behind the chickens’ names?

Yes! Most of the chickens are named after chickens here at the sanctuary, and all their names have some meaning. JoJo Eloise is named after my dad (Joe) and my grandma (Mary Eloise Boyd). My love of animals without question comes from my dad, and his from his mom. My grandma used to write children’s books, too. Often about children and animals. My dad taught me that animals were vulnerable and needed to be treated with the utmost care and gentleness. When I was a kid I used to get jealous of our cats because my dad loved them so much! Other chickens in the story include Satya, which means truth in Sanskrit, and Avi, named after the great bodhisattva of compassion Avalokiteshvaraya. And Abbie Metheny, the human ally, was inspired by two amazing women who run small chicken sanctuaries: Abbie Hubbard of Minnow and Blossom’s Place, and Anissa Metheny of Mother Cluckers Microsanctuary.

When Abbie finds Fannie sick and dying at Feed and Seed, the assistant manager didn’t have to let Abbie take Fannie or give her a free bag of food. Why did you feel it was important to make him an ally rather than an adversary?

I think the systems that these animals are trapped in—animal agriculture as a whole—and the corporations that are the bones of the system—corporations like Tyson, Perdue, Tractor Supply—are absolutely evil. But there are individuals working in these systems, working for the corporations, who are decent, compassionate people. I’ve met a few people working for Tractor Supply in particular who have expressed sympathy for the chicks that they sell. It’s true that the chicks they sell are shipped in the mail in both freezing and sweltering temps, and many don’t survive. I’ve had managers admit to me that they thought it was wrong. And I know lots of people who have been able to rescue some of those sick babies thanks to store managers who were moved by compassion to surrender them. I think most people really do have compassion and are conflicted by the way we treat those animals we consider food.

I love that the birds are the ones taking action, saving themselves while being supported by “human allies.” Why did you want Fannie to lead the charge rather than Abbie?

I don’t like the framing of human superiority. I think it’s simply wrong. But it’s also the case that we have a unique power, and the animals are at our mercy. But we aren’t superior or better. And I didn’t want the story just to be about good people saving helpless animals. I wanted it to be about the animals driving the change they want, and humans listening to their message. Though there are good people in the story. And in reality, of course, animals do need our help. But it’s like how we talk about the animals not having a voice. In truth, they absolutely have a voice. We just don’t listen or understand. So in the book I wanted to try to have the interests of the chickens themselves driving the story.

Of course, I write it so they are communicating in a way that might seem like anthropomorphizing to some, but I tried to communicate what I believe they are actually trying to tell us all the time. Basically just that they are sentient beings with their own interests, who want to live and to be treated with kindness. When I listen to the chickens talk, and they talk a lot, there are plenty of things I don’t entirely understand, but the closer attention I pay, with curiosity and respect, the more I understand. And it's very clear to me that they are pleading with us to treat them better. So in the story I tried to make that clear while being true to their genuine characters and interests.

Since birds like Fannie, regrettably, can’t testify before Congress themselves, how can humans best advocate for them?

I think we need to work for a world free of animal exploitation and speciesism, for an end to animal farming. I think we need to work for norm change, normalizing compassion and veganism. So a lot of the work that needs to be done is cultural, but then we also absolutely need to work for legal rights and protections. I think outlawing the worst practices of factory farms is certainly essential, but we need to go way beyond that. There are countries around the world that are starting to recognize animals as sentient beings deserving of legal protection, but as far as I know most of those protections still exclude farmed animals. The farmed animals suffer the most, in terms of numbers at least. Chickens are the most abused land animal on earth, which is a lot of why I focus on them in my own advocacy. Since people are starting to turn away from eating cows because of health and environmental concerns, a lot of people unfortunately will switch to eating chickens and fish, which may be better for health and the environment, but it’s still terrible by all measures when compared to eating plant-based foods. And when we switch from eating cows to eating chickens and sea creatures, we increase the total amount of animals who suffer and are killed. So I think being very mindful of that in our advocacy is also critical.

How did you decide that the chickens and humans would be able to speak to each other?

Here at my little sanctuary we talk to each other all the time. Everyone has a unique voice, and I do my best to hear them and communicate back in a way that they understand. Communication is about so much more than words. Most of us who’ve had relationships with dogs and cats know this. I know when the chickens see a predator, or if someone needs to find a spot to lay an egg, or when someone has just laid an egg, or when they’re hungry, or content, or irritated, etc. We don’t use the same lexicon, but there’s still so much we are able to communicate with each other if we’re paying attention, trying to understand, if we’re empathizing. Most humans aren’t. And that’s the problem. So I guess it just seemed natural and important that the humans and non-human animals should be able to communicate in the book.

In your novella Killing Them with Kindness, you wrote, “Olly wondered if these wild birds, diving and screaming like harpies overhead, could talk, and if so, what kinds of things they had on their minds.” You explore avian communication, albeit in a different way, in Chickens Are Animals, Too! What do you hope readers will take away from your books about animals and their ability to communicate?

Animals clearly communicate. The only real question is whether or not we’re listening or trying to understand. We often say that the animals have no voice, but that’s simply not true. They have voices, and they have a lot to say. The only real limitation is our interest and ability to understand. I want people to realize that the animals are communicating, that they have very clear interests. We might just start with the assumption that they want what we want. Because we’re not so different. We all want to live, to be free from suffering, to be treated with respect and dignity. And too, each species has its own species-specific interests, and each individual, regardless of species, has their own unique interests and desires. I hope readers will see that what the animals in my books express are not just fanciful anthropomorphic projections but a real effort to translate and convey the message the animals themselves are trying to send us.

[SPOILER] Killing Them with Kindness is one of the only stories I’ve read that realistically shows the simultaneous hope and cynicism of animal rights advocacy, as exemplified in Olly and Moon’s conversation about death—or annihilation—as a compassionate act. What inspired you to write about this?

I’m really against violence, and the idea of destroying the world is the ultimate violence, but there are times when the magnitude of the problem, of the suffering humans cause, seems too big to rein in, and it’s hard to imagine us making the changes we need to make, and I find my mind wandering off to that extreme thought experiment. There’s a part of me that can feel quite hopeless when I see the scope of the suffering and I see that the numbers of animals being killed are rising, and it seems that as the human population grows that we just scale up our destruction and exploitation and cruelty. Despite all of the knowledge that we have about the harms we’re doing to the animals and the planet, the threats even to our own health that come as a byproduct or unintended consequence of our exploitation, things like antibiotic resistance, and zoonotic pandemic risk, we just keep plowing ahead. And in those moments of total overwhelm, I still occasionally fantasize about some catastrophic, extinction-level event taking us out before we can do any more harm.

But I’d much rather that we solved the problems, and I’m not completely hopeless. I do believe that there are an increasing number of people who see the problem and know we need to change, that there are good, wise, compassionate people everywhere. We have a lot of serious obstacles to overcome, like ignorance, indifference, habit, greed, selfishness, ideas of superiority over each other, the animals, and the natural world. But ultimately I’m like Olly, and as long as there are beings in the world who want to live, who can experience joy and love and happiness, as long as there’s still the possibility that we can save the beings who suffer and create a better world, I would never push the button.

[SPOILER] Killing Them with Kindness opens with the narrator telling us that the protagonist, Olly, “is a very good man, a very kind man, one of the best men I’ve ever known. He just isn’t a great man, in the final analysis.” Without even knowing what happens in the rest of the story, many animal activists can probably relate to this sentiment, regarding people who are generally kind yet don’t seem to care about animal rights. But upon finishing the book and learning what the narrator really means here, there are still many activists who share his nihilistic perspective. How do you feel about his interpretation of greatness, compared to Olly’s?

When I was writing this, I was thinking about people like Socrates, the Buddha, and Jesus Christ, all people who left their own families to pursue a greater good for the whole, for human society or, like in the Buddha’s case, for all sentient beings. Leaving personal family behind, sacrificing those intimate family bonds seems like a necessary stage for many of these great historical figures who we associate with Universal love and the greater good.

Olly empathizes and feels compassion for the whole world and all beings who suffer, but his personal ties and relationships are still, in the end, I think what moves him more than anything. So in some way, he puts his family before the whole. And ultimately his motivation is to protect them. I believe that the ultimate spiritual goal is to love all beings without discrimination or preference, to realize that the life of the little girl on the other side of the world is of equal value to that of our own daughters, that the dogs in laboratories deserve to be free from cruel experimentation just as much as our own dogs do, that all sentient beings equally deserve peace and freedom, and that we should all strive to love all beings as if they were our own families. But that said, I also believe it's a very natural quality of the heart that we love “our own” the deepest. And we can use that kind of deep, unconditional love as a starting place and a springboard to expand our love out all the way to embrace the whole. This is the foundation of a loving-kindness practice.

The narrator thinks that Olly chose to protect his family at the expense of doing what was necessary to end the suffering of all other beings, and that’s why the narrator concludes that Olly was good, but not great. But I think Olly’s choice to protect his own family wasn’t just selfish, or small, as the narrator implies, but the individuals in his immediate circle represent all others. He wasn’t able to make the ultimate sacrifice, which the narrator sees as a personal weakness, but Olly’s motivation was love. For his family foremost, yes, but it’s clear through the story I think that Olly’s love extends far out beyond that. Even when he tries to run away from the world, he can’t ignore the suffering that continues out there. His love and compassion really do embrace the whole. And I think in the end, Olly looked out and he saw beautiful beings who were filled with joy, and he saw a beautiful world worth saving, despite the suffering.

Other Work

Can you share a little bit about your work with ARC and Sweet Peeps Microsanctuary?

I started ARC in 2016, I think. I had moved to Alabama a few years earlier, and there was nothing here in terms of animal rights. I started organizing a few local events like a circus protest, and I was doing some vegan cooking classes and a vegan meal delivery service. But it was when I went to Plum Village Monastery in France to do a retreat with the Zen Buddhist teacher Thich Nhat Hanh—Thay, as his students called him—that I decided to start ARC. During the retreat, I had an opportunity to ask Thay a question during one of the Q&A sessions. I asked him what was the best thing we could do to help the animals. First, he told me we could not allow ourselves to drown in sorrow or else we couldn’t help anyone, so he said we need a practice to keep us afloat, and then he said I should find like-minded people and work together with them for the animals, rather than trying to do everything on my own. So I came home and got together with some compassionate vegan friends in the community, and we started ARC. Mostly we do vegan advocacy, dinners, and host educational speakers and events, but we also do things like rodeo and circus protests.

In January of 2019, a chicken farm in Colorado went bankrupt, turned off their heat and stopped feeding the 40,000 birds in their sheds. A local sanctuary, Luvin Arms, found out what was happening and they sounded the alarm to the animal rights community. Activists traveled cross country to help rescue as many birds as possible, but they needed homes for the rescued birds. I knew nothing about chickens, but when I saw something come across my Facebook feed, I volunteered to take a couple. I ended up taking eight. And that was the beginning of Sweet Peeps. Since then, I’ve moved out to the country so I’d have more space for them, and have rescued about 30 others. Almost all the original Sweet Peeps are still here. But I lost my Fannie this past year. She was one of the original Sweet Peeps and the inspiration for the main character in Chickens. She was the first chicken to teach me what incredible people chickens are. Fannie was one of the great loves of my life. I miss her terribly every single day. She loved me as much as I loved her. She will forever live on in my heart and in all the work I do for her kind.

At present, we have 26 chickens (including a brand new baby who jumped off a slaughter truck), plus 17 cats, and one very good dog. All but two of the chickens are Cornish Crosses, the breed used by the meat industry. Cornishes are very different from other chickens. They’ve been extremely genetically manipulated by the meat industry to be slaughter-weight by the time they’re just six weeks old. They aren't bred for good health or longevity. So trying to ensure they have long, healthy lives involves a lot of breed-specific considerations and special care. But these are some of the sweetest animals I’ve ever known. In order to ensure they receive the care they need, I had to start hiring help a few years back. It just got to be more than I could handle on my own. It’s now a full time job and then some.

What are the differences between having a microsanctuary and having “backyard chickens”?

The difference between backyard chickens and microsanctuaries is the difference between seeing chickens as expendable commodities to be exploited and seeing them as sentient beings just as deserving of our love and care as other companion animals like dogs and cats. When I first saw that post about the bankrupt chicken farm in CO and was trying to decide whether I could take any of the chickens, I did a little research online about taking care of chickens. That led me to a bunch of backyard chicken groups which all said that keeping chickens was cheap and easy. Ha! It turns out this is only the case if they, as individuals, are expendable. Thankfully, I was already connected to people in the sanctuary community who quickly educated me about truly compassionate care for chickens. If I had relied solely on the backyard chicken resources I found, there is no chance any of those original CO girls would still be with me.

Most backyard chicken keepers still see their chickens as a commodity. They purchase and sell chickens. And although some people will say they love their chickens, the truth is they mostly keep hens for their eggs and will keep maybe one rooster for every six or seven hens. Because 50% of all chickens who hatch are roosters, that's a lot of missing roosters. Roosters are often killed outright by hatcheries, and are dumped all the time. And they don’t survive long when they’re dumped.

Most backyard chicken keepers don’t believe in taking chickens to a veterinarian, and so chickens in backyard flocks get sick and die as a matter of course from illnesses that could be treated with proper veterinary care. There is also a widespread mentality in backyard chicken circles that as long as a chicken is surviving, that’s good enough. In contrast, in the microsanctuary community, we are committed to doing all we can to make sure the animals in our care don’t just survive, but thrive.

Basically, backyard chickens are most often still victims of speciesism, receiving substandard care because they are viewed as less than other animals. They are exploited for their bodies and by-products, depersonalized, seen as less than other species. Whereas, in a microsanctuary setting, residents are given the highest level of care that each individual needs in order to be healthy, safe, and to thrive. They are treated with dignity, respect, and an understanding that they are of equal inherent value.

What drew you to chickens?

I went vegan almost 20 years ago, and knew even before then that what we do to chickens is an atrocity. But even after being vegan for more than a decade, I realized I didn’t really know chickens, and I didn’t feel the same level of connection with them that I did with other species like dogs and cats, or cows and pigs. I sensed that I was missing something, that if I knew them better, I could be a better advocate for them, and with chickens representing 90% of the land animals who are killed for food every year, I knew they should be at the center of our vegan advocacy. So for years, in the back of my mind, I’d had an idea that one day I wanted to rescue chickens and get to know them better.

When I saw that post about the bankrupt chicken farm, the time was just right. My dad had died about two months before, and I was living in his house, which had an empty shed on the property. My life had been pretty consumed with taking care of him in the last couple years of his life, and I was eager to redirect my energy to the animals now that my dad was gone. So when I saw that post, I just felt compelled to help. I realized quickly that they were neither cheap nor easy to care for, despite what those backyard chicken forums had promised. But I had committed to them, so I did what was necessary to give them the best life possible, which really meant changing my life to revolve around them. And it turns out I was entirely correct that the more I got to know them, the more I would want to advocate for them. They are all individuals with rich, endearing personalities. They are smart, funny, sweet, sometimes sassy, peaceful, joyful beings, capable of great suffering and great happiness. I really had no idea who they were or how deeply I would fall in love with them. Now I just want the world to know what I know.

Final Questions

How can readers find you and your stories online?

People can find all of my books through my website.

Any upcoming projects?

Yes! I have another children’s book, something of a prequel to Chickens Are Animals, Too! that is scheduled to be published in the Spring of 2025 through 12 Willows Press, which is the same publisher who published Chickens. I have a non-fiction book that I completed a while back that is currently in the hands of another publisher, who, fingers crossed, is going to publish it, but I don’t think that will be before 2027. I’ve also just started working on a new film looking at the chicken industry. I’m hoping it will be a feature-length film, but it’s in the very early stages, and I currently have zero budget, so a lot is yet to be determined. But I have already started filming so something is in the works!

Anything else you’d like to share?

Thank you so much for the opportunity to talk about my work. These have been wonderful, thoughtful questions!

Okay, I included that last one because it made me feel good!

Thank you so much for this, Elise! I really loved having this conversation. All of your questions were so perceptive and insightful and just went right to the heart of what I was trying to convey with my writing. I so appreciated the opportunity to dive into all of this!