Welcome back to another Wizard of Claws interview!

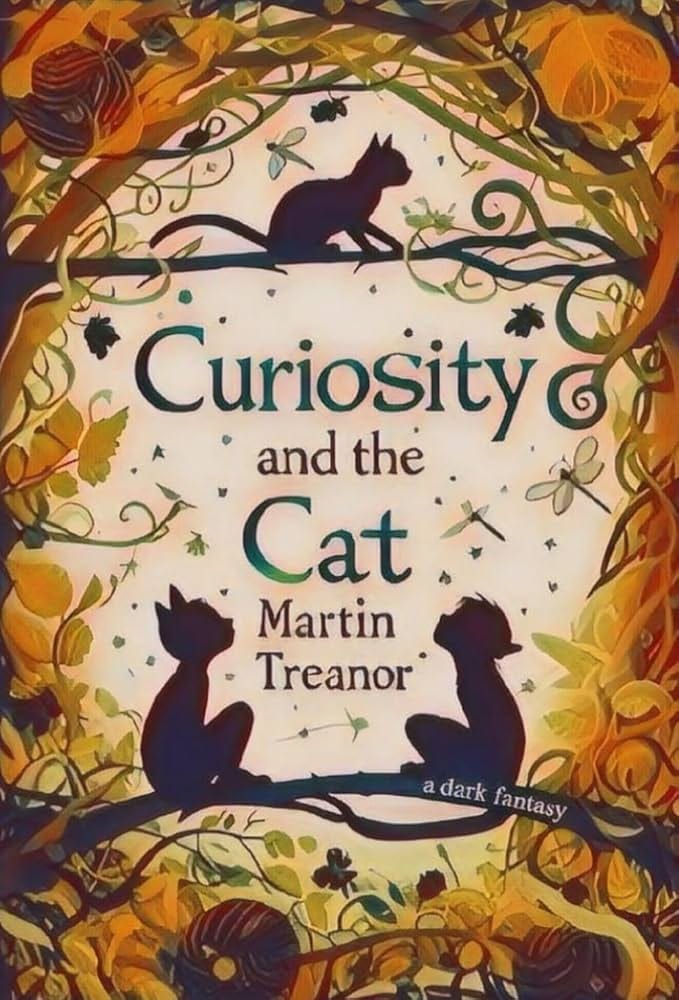

For those of us who grew up watching Disney Princess movies, fairies were cute, benevolent ladies with sparkly wings and magic wands. But the fae folk in Martin Treanor’s novel Curiosity and the Cat are of a much older, more traditional (and downright spooky) variety. They are agents of the natural world, and they do not take kindly to human interference in their land. Then along comes Curiosity, our eponymous little protagonist, who discovers that there are faeries living in her very garden…

General Questions

Can you share a little bit about yourself, including how you came to care about animals and creative writing?

I’m originally from Ireland and now (having moved around quite a bit) live in Portugal with my wife, Lynsey, and an insanely adorable but overdramatic cat, Kitty. I became vegan thirteen years ago and, by then, had been writing for a couple of decades. It was through this transition, however, that I began to see how prevalent and gratuitous animal exploitation was embedded in the fiction we read, watch, and listen to.

Many of us have childhood dreams of becoming a writer. When did you decide to give it a shot?

Professionally I am an engineer (and have had a number of occupations over the years) but I always illustrated and painted which, in turn, was enhanced by my love of reading. When I moved to Denmark — perhaps because of the newness of the situation — one day, I just sat down at the PC and began a story. It felt like illustrating, but with a wider focus . . . and I was hooked.

Most animal advocacy focuses on creating tangible changes in the real world. What role can the arts play in changing how people think about animals?

For my part, I would like to (and do) remove the seemingly normal ‘animals as meals’ aspects of fiction writing. Particularly within the fantasy genre, where it seems to be all but obligatory. And I find it just as easy to not include such things. As for the arts in general, if I can do so when writing, anyone can with any other medium. It’s not that hard. My hope is that I begin a new tradition of not mentioning the characters eating at all . . . or, if they have to for the narrative, giving them a non-animal alternative.

What does a typical day of writing look like for you?

First big statement: I am in no way a morning person. I get up around 9.30/10.00 and take a slow start into the day. I usually begin writing around 1pm, and continue until around 6/7pm-ish — I then do a bit on the way to bed, which is usually in the wee hours. Not the normal day, but it works for my weirdo mind.

As an American, I’m impressed that people in other countries follow our national politics. (I can barely keep up with it myself!) What inspired you to write the Trumplethinskin books? (Awesome title, btw.)

Actually, it was my publisher in early 2020 who sent an email saying, ‘The US election is coming up, you’re all writers, so write something.’

Because I follow US politics — as do many in Europe (because of The USA’s influence on global affairs) — I had enough knowledge of Trump’s history to put together a short (200 word) piece in the style of a children’s picture book. My publisher wrote back instantly, said, ‘Make this about a 1000 words. Do 3 books . . . oh, and you’re illustrating them too.’

Now, who could turn down an opportunity like that?

Story Questions

This story is a dark fantasy, but I’d say it’s also at least partly eco-horror. When you began working on the novel, which came first: the theme or the plot?

With all of my books, it’s always the theme. Stephen King calls it the what-if? And, to Irish people like myself, the sídhe (faeries) have always been there. So, by extension, I think I always wanted to do a book about faeries at the bottom of the garden, only with an Irish/Celtic flair; where they are magical, but also scary, manipulative, not open to reasoning.

Another theme I enjoyed in the book is that magic can be found anywhere. Whether it’s in a secret toy shop or in our backyards, there are little worlds hidden all around us. But we rarely look. The narrator even says something to this effect: “I consider all the creatures of this good earth to be much more than their outward appearances. All too often, what the world sees becomes a means to pigeonhole a person or creature into some arbitrary identifiable but faceless subcategory.” How can looking deeper at animals, nature, and other humans help us reconnect with the magic of life?

Because that’s where it's at. It’s where we, and all things, are. We are products of and beholden to the natural world around us. The narrator, in this case, is just telling it like it is. As part of nature, we have an obligation to protect nature. As mentioned above, the world of the sídhe is a magical one but also a natural one. They are also easy to anger if the natural world is ignored or overexploited. There is a message there. To my mind, it would be good to heed it.

Late in the book, a faerie says, “Cats are precious. We like to think of them as our window to the world. Spies, if you like…familiars.” Why do you think we associate cats in particular with magic?

Show me a writer, and they’ll definitely share their home with a cat. Or want to. So, is it the cat or the writer who makes that decision? In my opinion, cats are the perfect beings: hearing, sight, agility, speed, the way they can manipulate their bodies, and do that alternating radar-dish thing they do with their ears. It’s as if they are not of this Earth. Supernatural entities? An alien species? They are definitely intriguing and, when they deign to grace you with their presence, a delight to have around. Exactly how they want it.

Faeries are having a moment right now. Why can’t readers get enough of faerie stories?

Coming from Ireland, and a country area at that, our whole folklore is steeped in stories of the sídhe. They are the underfolk. The tricksters. The entities who, if you annoy them or trespass in one of their spaces, will steal your children and make your life hell. And these types of stories are timeless and universal. Every culture has similar beings and tales. I think the recent interest in faeries is because the tale (and some might say the faeries themselves) never truly went away. In fiction, readers like stories that tap into the collective psyche, and archetype. Our job as writers is to give them that.

Did you create the book’s illustrations before you started writing, during the writing process, or after finishing the manuscript? In your opinion, what do images add to a story?

Actually, I did the illustrations afterwards, but had always intended to do a few to add a visual aspect to the story. The book was inspired, not only by the tales I grew up with, but by the storybooks I read as a child. And they always had a visual aspect. I thought it important to give the same to the reader . . . to hopefully evoke memories of childhood, where they too could see themselves at the bottom of the garden, unknowing of the watchful eyes of the faerie-folk.

If there’s some sort of gene that causes a person to like spooky stuff, then I must have it. In the community of Halloween, horror, and spooky lovers, animals that were once reviled — cats, bats, rats, toads, snakes, spiders — are now beloved. In what ways can fan culture benefit animals?

Ah, that’s it, though, isn’t it? All animals are what they are, it was only human misperceptions that made them spooky, creepy, and scary. What has happened now, however, by way of better understanding and/or because of our more caring nature coming to the fore, is that the once maligned creatures have become cool. And as fan-culture geeks — and vegans, no less — we can make them even cooler. I mean, who doesn't love a black cat or a chirpy little rat? We should always show the world how great they are.

The narrator finishes the tale by saying, “I heartily wish you only good fortune as you contemplate the myriad of living things that call this ball of rock, earth, and verdure home.” What do you hope readers will learn from Curiosity’s story?

In a nutshell, respect for nature and everything that lives. It’s what the faeries do. They are part of and custodians of nature — as are we. We should remember this. And do everything in our power to make the world a safe home for everything that lives in it. I like to think, in their own way, every character in the book learned this lesson. It’s why they endured so much. To learn. To be kinder. And to know of the consequences for thwarting nature.

Final Questions

How can readers find you and your stories online?

My books are available in all formats from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, GoogleBooks, and anywhere that sells books.

Quick links can be found via my Linktree.

My general website is: MartinTreanor.com

My Goodreads is: Martin Treanor | Goodreads

Instagram/Facebook/Threads: @martintreanorauthor

Bluesky: @martintreanor.bsky.social

Any upcoming projects?

I am currently working on two projects:

Running down the last edits on the first novel in an epic fantasy series (this is where I really want to address animal exploitation in fiction).

Starting the second draft of a story about a homeless woman caught up in the policy of a newly minted fascist government in Ireland.

I have no publisher for these, as yet, so will be embarking on the submission process again.

Anything else you’d like to share?

I’d like to share a quote from the late, great Benjamin Zephaniah:

‘Many of us live with companion animals such as dogs, cats, and rabbits. We share our homes with them, consider them members of the family and we grieve when they die. Yet we kill and eat other animals who, if you really think about it, are no different from the ones we love.’