“Angry tears have magic in them.”

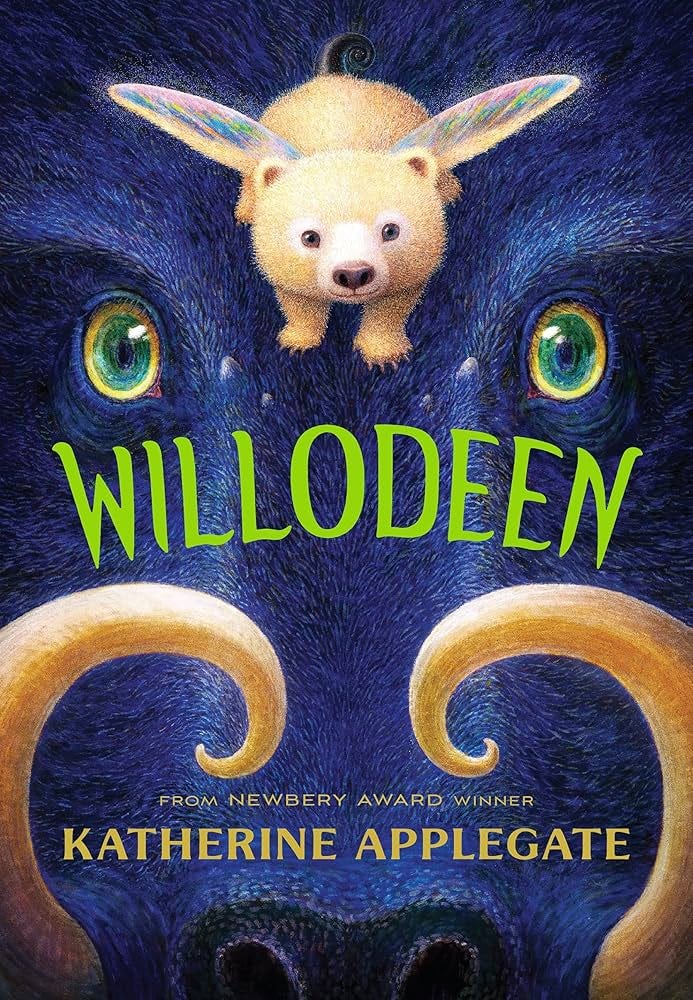

If you’re looking for a gift for a young reader in your life, look no further than Willodeen by Katherine Applegate. A middle-grade novel set in a fantasy world, eleven-year-old Willodeen uses her love of animals to save local wildlife and teach her fellow villagers about the importance of biodiversity.

After losing her family and home in a wildfire, neighbors in Willodeen’s village take her in. Alone, she continues her walks through the woods without her father, observing and documenting the wildlife she sees. One day she comes across a dying screecher—an animal much like a wild boar, though they scream rather loudly and smell quite foul—and names him Sir Zurt. Hunters approach, and we learn that the town’s put a bounty on the head of each dead screecher.

A tourist town, their economy relies on the annual migration of hummingbears—like sentient, winged teddy bears who build nests in trees out of bubbles—but the hummingbears haven’t shown up this year, and numbers have steadily declined for a while. As she cares for a baby screecher, Willodeen learns that the near-extinction of screechers is to blame for the absence of hummingbears. By raising awareness of this issue, Willodeen manages to save screechers, hummingbears, and the village itself.

Willodeen’s Misbelief

Lisa Cron writes in Story Genius, her step-by-step guide for developing a novel, that every protagonist is fueled by their misbelief. Basically, a misbelief is the defining principle upon which their entire view of the world is based, but unlike a regular belief, a misbelief is fundamentally flawed in some way. For Willodeen, that misbelief is that she’s an outcast. She retreats into the woods with animals because she assumes nobody likes—or, more importantly, understands—her.

It’s not an entirely unfounded claim, which is what makes misbeliefs so pernicious. Willodeen tells us in the second chapter,

“I suppose I always loved strange beasts. Even as a wee child, I was drawn to them.

“The scarier, the smellier, the uglier, the better.

“Of course, I was kindly disposed toward all of earth’s creatures. Birds and bats, toads and cats, slimy and scaly, noble and humble.

“But I especially loved the unlovable ones. The ones folks called pests. Vermin. Monsters, even.”

She knows she’s different, and while she doesn’t try to change that part of herself, she does try to hide it. Avoiding others at all costs and looking down at her feet when she has to interact with people, she feeds her misbelief through avoidance. (I can relate.)

Bringing Her Misbelief to Life

At a town council meeting early in the book, the usually quiet Willodeen bursts out in a rage over the town’s treatment of screechers:

“‘These animals…screechers…they’re as much a part of things as you and me…. Look, I don’t know why the hummingbears are gone. I don’t know why the world is changing so fast and so wrong. But I do know that nature’s a complicated thing. It’s like…it’s like, I don’t know, like knitting a sweater. You pull on a string too hard, and the whole thing starts unraveling. I’m just saying let’s not lose things before we get the chance to understand them. Screechers included.’

“Silence.

“Murmurs.

“Laughter.

“It was time to leave.”

Afterward, alone, ashamed, she cries. She laments how odd and unloveable she is. And readers’ hearts break. Who among us—especially as activists—hasn’t felt the sting of rejection? For a young girl who’s lost her family, lost that connection with her father who loved animals as much as she, the cold apathy toward her pleas for peace is like a screecher tusk to the heart.

Even if readers may not feel the same love for screechers as Willodeen—how could we? they’re not actually real—her interaction with Sir Zurt and the hunters shows us how people in this town treat screechers and how much that hurts Willodeen. It makes her feel more isolated, more downtrodden. For many of us, it’s hard to imagine that just one person speaking up can really make a difference, especially in the face of such adversity.

And Willodeen believes that, too. She interprets the silence, murmurs, and laughter as a negative, and while we know the villagers don’t care about screechers themselves, she flees the scene before she can be dismissed or encouraged to say more. Her mind made up about her own self-worth, she retreats back into herself.

While her misbelief preexists the events of the story, it was just reinforced in front of the entire town.

10 Animal Archetypes in the Fantasy Genre

Animals exist before, between, and after “once upon a time” and “the end.” They breathe life into stories, and they add dimension to the background of fictional universes, making fantasy lands feel real.

Willodeen’s Empathy

We empathize with Willodeen because we connect with her misbelief, and by reading the story through her perspective we also come to empathize with the creatures she cares about. When she finds Sir Zurt in the woods, she describes his limp as being like that of her elderly guardians. This humanizes screechers, gives them personality and vulnerability, and suddenly we’ve switched from being ambivalent about them to rooting for this one to survive.

He doesn’t. And that draws us to Willodeen’s side even more.

Her Misbelief Threatens Her Empathy

After the council meeting, Willodeen says she shouldn’t have spoken up in defense of screechers, that it’s futile to even try to help them because nobody cares about them. All they care about is hummingbears. And we’re right there with her; we feel her despair. Hummingbears are fuzzy and adorable and easily loveable, but we’ve seen the horrors screechers face due to their bristly nature. We’re rooting for her, thinking, Don’t give up, Willodeen. You did the right thing!

Applegate uses our own bias to favor cute and cuddly animals over ones that are less so to hammer the point home. In the real world, we protect beautiful animals and discard the ones who don’t meet our aesthetic ideals. Even the book’s cover highlights this prejudice, with a menacing screecher shadowed behind a bright hummingbear.

By being on Willodeen’s side, readers can more freely explore their own biases against certain species. Maybe next time they won’t scrunch their nose at a raccoon rooting through refuse but stop to think about how resourceful and resilient raccoons truly are. Hopefully, they’ll also want to become animal activists or reconsider any prejudice they have against activists.

Willodeen’s Relatability

Reading is an inherently empathetic act. You must share a mind with the protagonist to understand why they do what they do. And that mind-melding lingers, especially when a character confronts one of your own misbeliefs.

I personally find Willodeen relatable in many ways, but even the average reader can relate to the book’s broad theme of an outcast coming into her own by accepting her quirks rather than hiding them. But there’s one misbelief in this novel that blurs the line between reader and story.

After finding Sir Zurt, Willodeen thinks,

“My parents had taught me to hunt. I ate rabbit stew and chicken when I could, same as everyone else.

“But to kill something for no reason, just because? Where was the sense in that?”

I initially rolled my eyes at these lines, but upon reflection, I think this makes Willodeen even more relatable to the average reader. If she’d been strictly herbivorous, the concept of eating animals may not have even been mentioned and, if it had, likely would’ve put some readers on the defensive. Willodeen, therefore, becomes an ally, and she and the reader can explore together the ethics of eating animals.

Her Misbelief Makes Her Relatable

For all her awkwardness and self-consciousness, Willodeen is not a passive person:

“Maybe when the whole world was marching one way, some ornery part of me started shouting Go the other way, Willodeen.”

She thinks critically about everything and always seeks to empathize with animals:

When handling an arrow from one of the hunters who killed Sir Zurt, she imagines “the pain it could inflict” and reflects on how she’s done that to the animals she’s hunted.

The baby screecher she cares for, Quinby, will only eat a particular kind of snail. “‘I feel guilty about the snails,’ [Willodeen] admitted. ‘They’re so pretty. And there they were, minding their own business, until I came along.’”

Willodeen puts Quinby in a harness to protect her while they go out hunting for snails, but Willodeen says, “It doesn’t feel right, having a wild thing tied up.”

Willodeen never simply accepts that certain animals are unworthy of compassion, nor that it’s permissible to treat ugly, nuisance beasts with less care and affection than others.

Notably, Willodeen learns something else over the course of the story—that “usefulness” is not always objective or obvious. When a new friend makes her a screecher doll, she thinks, “This served no purpose. And yet…and yet it made me smile.” In this moment, she learns that art’s “usefulness” is its beauty and the joy it brings to the maker and observers. The rest of the town comes to understand this same thing about screechers. Before her mother’s death, her mother, sharing the opinion of most of the town, says, “Can’t eat [screechers]. Taste like they smell. Useless a critter as I ever met.” By the end of the novel, though, Willodeen teaches the rest of the villagers that screechers are useful. Because they keep the snail population in check around the trees where the hummingbears like to nest, they’re essential to keeping the trees and wildlife alive. The town wasn’t able to see screechers’ usefulness because they didn’t directly gain anything from their existence—but Willodeen could see it.

Willodeen already cared about screechers, regardless of their essential role in the ecosystem, but by the end she realizes that her dad’s axiom, “Nature knows more than we do,” is true.

Willodeen always seeks to learn and grow, and she’s not afraid to confront her own misbeliefs. So, while she does eat some animals, she’s cognizant of her inconsistencies and isn’t content to simply sit back and accept the status quo. If more people were like this little girl in the real world, the future for animals would look far brighter than it does today.

More than anything, Willodeen’s just a regular kid trying to do the right thing. I’d like to think that children who read this book—and the adults who read it with them—will reflect on what Willodeen says and internalize it. Willodeen lives in a fantasy world without access to veggie burgers and oat milk, but what about me? Am I hurting animals for no reason? This is where the empathy we’ve built for both Willodeen and the screechers comes into play, asking readers to ponder what the screechers are in their lives.

Willodeen’s Belief

Willodeen overcomes her misbelief not by changing who she is at heart but by leaning into it. The things she initially perceived as weaknesses and oddities became the very things that saved her favorite animals and her town. Using her compassion for screechers, she’s able to see issues threatening everyone’s lives that no one else could’ve imagined were possible.

Her Misbelief Forces Her to Grow

At the end of the book, another wildfire threatens to destroy the town, but, despite their differences, everyone works together to put it out.

A council meeting convenes the following day, and there’s a quiet camaraderie among the townsfolk. Yet the council leader doesn’t miss the opportunity to take a swipe at Willodeen when she stands up to argue her case for protecting screechers. She has every right to hurl insults at him and everyone else for their ignorance, but she doesn’t. Instead, she clearly and concisely explains why the town needs screechers to protect hummingbears and, in turn, protect their own livelihoods.

I think this is what most animal advocates misunderstand about activism. The vast majority of people don’t consider ethics as deeply as we do on a daily basis; they’re just trying to live their lives. Creating a message based on what they want to hear—rather than only what we want to say—will be far more persuasive because it’ll naturally appeal to them.

Sure, Willodeen probably would’ve preferred if everyone chose to save screechers on their own merits, but she understood that her audience—the council members and other villagers—needed a reason relevant to their own lives. She also recognizes that the relationship she has with animals is special. Not everyone will understand it or grow to feel the same affection for screechers. And that’s okay. She’s not pressuring them to change who they are; as long as they’re not hurting screechers, she can accept being the odd duck fighting for them from the sidelines.

Willodeen in the Real World

Willodeen offers insights into how we can become better activists and how we can better understand the people we’re trying to reach. Choosing causes that are especially important to us—not to the movement or anyone else—adds authenticity to our activism, and makes it more palatable to our audience.

Viewing those people as human beings with their own experiences, principles, and interests—rather than as animal-abusing monsters—helps us empathize with them more. As

says in her memoir Always Too Much and Never Enough, “On some level, we are each just a product of our upbringing—of the people, places, and things that shaped us early on.” The more we understand what shaped their beliefs and misbeliefs, the more effective our messaging can be.Though her loved ones may not be as devoted to protecting animals as Willodeen, they support her and stand beside her when she stands up to the council.

In a way, Willodeen is the best messenger for this lesson. A child, she consistently underestimates her own ability to influence the people around her but tries to do so anyway. She represents the innocence and fierce devotion to her principles that many of us lose with age. She can make us all wonder…

“If horrible things were possible, why not magical ones?”

On my mind: the state of activism

Oof, trying to edit this after the election has been tough. Since 8:00 PM Tuesday night, I’ve spent about half the time on the verge of tears and glowering at anyone who smiled at me. My mind’s overwhelmed with thoughts of RFK Jr. banning vaccines and killing children, the dissolution of the Environmental Protection Agency and Department of Education, and a monstrous black hole looming before my country and the world for, at least, the next four years. (God willing we’re all allowed to vote again in 2028.)

I wrote this whole post with hope for a better future for activism, but in a time when our former/future president wants to deploy the military against activists, I worry about our ability to protest injustice. God, I hope I’m wrong. I so hope I’m wrong. But if I’m not, we’ll all have to be braver than we’ve ever been before to stand up for our own rights in addition to the rights of animals.

Willodeen gives me strength to believe that even in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, goodness will prevail.

“Change is coming, certain as sunrise. The only question is how we deal with it.”